Autonomous mobility is about more than the potential of self-driving cars. It involves a quiet technological revolution that’s similar to the one we underwent when moving from horse and buggy as a means of transport to the advent of the car. This early transition took about 40 years to complete. And, when it comes to autonomous mobility, we’re only in the first decade of this gradual shift from human-driven vehicles to autonomous vehicles, a period that has been marked by remarkable advances in technology as well as a significant shift in societal acceptance.

Within this initial period, we can already start to see these new technologies in use for passenger transport as well as the logistics industry, such as:

- Public transportation (Copenhagen’s subway)

- High-speed rail (Fuxing bullet train)

- Busses (Deutsche Bahn and IOKI)

- Delivery robots (Starship delivery robots).

Based on similar transitions, we’re likely to see, in the next decade or two, an increase in the types of autonomous mobility as well. In fact, companies are already starting to develop things like autonomous mining equipment, drones, freight trucks, ships, and agricultural equipment, among others.

New types of autonomous vehicles will also enable the world to move people, cargo, raw materials, and goods around the globe much faster than we can today. By diverting goods to new modes of transportation, new technologies can also help to ease the strain on labor markets. This includes entirely new forms of transportation, such as cargo drones that have already started to appear in Europe or autonomous freight trucking. The result is cheaper, greener, and more affordable global products.

Yet, looking from this very early perspective, the advances we’ve witnessed over the past decade appear to be isolated or one-off breakthroughs. An autonomous bus here or a self-driving train there, but not the kind of technology that we see on a daily basis. And, it’s hard to understand what’s holding us back as autonomous technology could greatly benefit a number of global markets.

Answering that is just as complex: we already have the technology, so to speak. It’s just that autonomy doesn’t look or work like we expect it to. There are still a number of barriers that we need to overcome before driverless vehicles become part of our everyday lives. One of these barriers includes the transition to higher levels of autonomy.

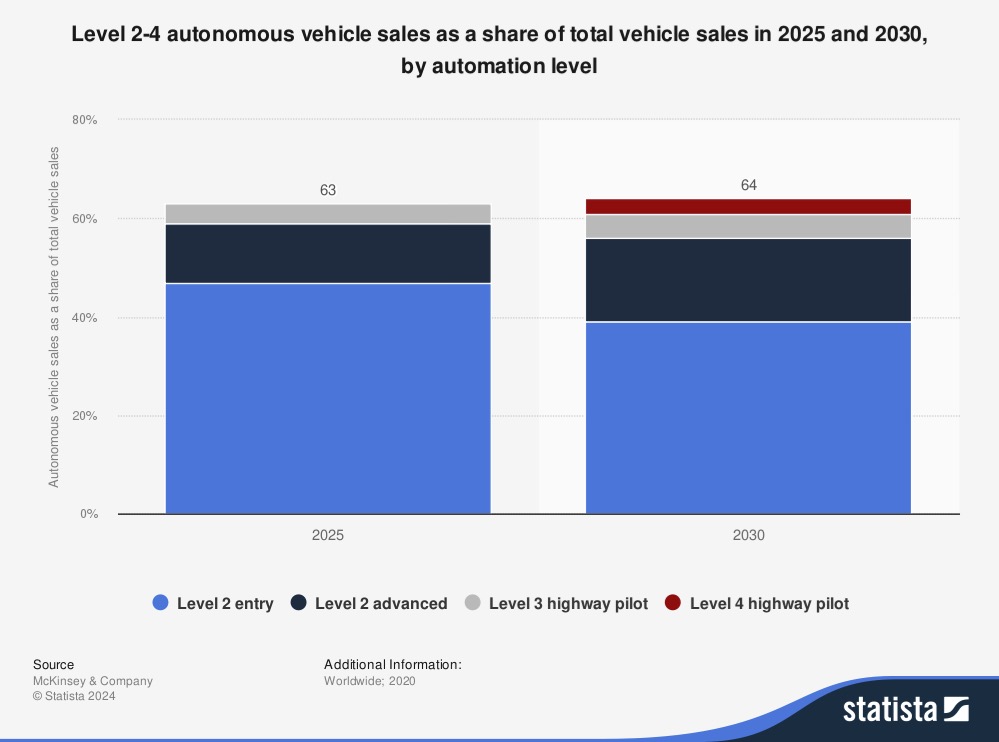

The majority of our vehicles have some level of automation that we have come to trust, which is true for both the automotive and aviation industries (think of cruise control or a plane’s autopilot). As of 2019, there were approximately 31 million cars with at least some level of automation, and that number is expected to reach 54 million later this year, according to a study published by Statista. A simple example of this is the fact that almost all the people in the United States today learn how to drive with the help of automatic cars that shift gears. It was also in 1948 that cruise control was invented, making this automotive automation older than many people alive today. Full automation is on its way, but it’s going to take a long time before we’re sitting in fully autonomous cars, and it’s hard to predict exactly when that will happen.

Currently, we judge how far autonomy is based on a scale of five levels of autonomy: Level zero, no autonomy; level one, driver assistance; level two, partially autonomous driving; level three, conditional automation; level four, high automation; and, level five, full automation.

Early innovations aren’t always going to be perfect, either. Some people have already been injured by autonomous passenger vehicles. Regulators are also aware of that. That’s why progress in allowing higher levels of automation has been pretty slow, even if the technology exists. Companies are now expected to prove that they can provide reliable products and services at higher levels of automation.

However, until fully autonomous vehicles are able to prove their safety standards, it is likely that public acceptance will continue to be low or even decline if there are further incidents. That’s likely why the state of the current level of trust isn’t looking good, either. Consumer trust and familiarity with autonomous vehicles remain the biggest barriers to the adoption of fully autonomous transportation, according to the Spring 2023 S&P Global Mobility Survey. More specifically, the survey found that as the level of autonomy increases, consumers become less inclined to buy. This goes against what governments and regulators are hoping for as they push to reduce pollution and congestion through increased autonomy in cities.

Although some autonomous vehicles (like freight trucks) still will use fossil fuels, the fluidity of AI systems in driving is linked to fewer emissions and less air pollution. This includes noise pollution as well due to reduced honking frequencies, which, thankfully, are unlikely to be programmed at the same frequency as human drivers. Additionally, as more and more autonomous vehicles are added, these can be routed through Traffic Intelligence Systems (TIS), which are able to forecast and reroute vehicles to increase energy efficiency while reducing emissions and pollution.

During the process of implementing wide-scale Traffic Intelligence Systems in the freight industry, autonomous vehicles only meant to carry material goods will also very likely be redesigned, removing safety features meant for human drivers that currently weigh down the vehicles considerably, making them less fuel-efficient and oftentimes bulky. These safety features would only then need to be included in autonomous vehicles made for passenger transportation, allowing for further optimization in the logistics industry.

The slow acceptance of autonomous mobility

While it might seem strange that public acceptance is so low for autonomous mobility, it’s not the first time we’ve seen this type of backlash. Introducing the private car didn’t go smoothly, either. Actually, if you take a look back at the history of introducing new forms of mobility, you might stumble across an entire hidden history of anti-automobile protests in the Netherlands that shaped the country’s infrastructure to this day. Surprisingly, these protests also happened in the U.S., which sought to eliminate the use of automobiles by arguing that they created an unsafe environment for children, who could likely be run over. While their European counterparts did succeed in shaping the future of the Netherlands (you see this today in the extensive network of bike lanes and trains), the American protestors were more isolated in the United States due to long distances, leading to the protests dying out a few decades after the Second World War.

It might sound entertaining, considering how car-focused Americans are today, but there is nothing particularly unusual about this kind of backlash against new technology. It’s happened from well before the invention of the tractor to the advent of the cell phone. And, we’re seeing it now with the backlash against electric cars and autonomous freight trucking. But, it would be wrong to think of this as a potential barrier to innovation. Backlash is actually a normal part of introducing new technology, according to Harvard professor Caletostous Juma:

society tends to reject new technologies when they substitute for, rather than augment, our humanity.

And, it’s pretty hard to argue against autonomous cars and freight trucks substituting human drivers. While rejection is a part of the initial cycle of introducing new technologies, it isn’t the only setback to adopting them.

When implementing autonomous mobility goes wrong

In 2015, many were concerned that the state of autonomous driving technology wasn’t ready to be fully relied upon when a Tesla driver died watching Harry Potter during an autopilot malfunction. Four years later, another person was killed after the autopilot of a Tesla caused the car to crash into a tree. As of June 2023, a total of 17 deaths related to Tesla’s autopilot have been reported in the United States.

Many of these problems have also been caused by the changes in recent models, like the removal of some radars and the increase in new features. These changes have also prompted an organization to release two ads during the Super Bowl to boycott the technology. The ads show footage of the autopilot malfunctioning in everyday situations involving dummy figures of both children and adults (Ad 1 and Ad 2).

Tesla isn’t the only company to bear the blame for moving too fast. Driverless taxi company Cruise also had a software feature that resulted in devastating consequences. A woman walking on the street was struck by a human-driven car and propelled in front of an autonomous Cruise vehicle. Due to the lack of instructions in the software for such an incident, the car proceeded to pull over. Due to traffic and parking possibilities, the woman was then dragged 20 feet to a curb before the vehicle parked itself on top of her, forcing emergency responders to use the jaws of life to pull her out. Given the violent nature of the incident, many people grew increasingly concerned about whether fully autonomous vehicles are safe at this stage of development. For those curious, the woman survived, and Cruise is no longer allowed to operate while they undergo an ongoing investigation into the events.

The current state of acceptance for autonomous mobility

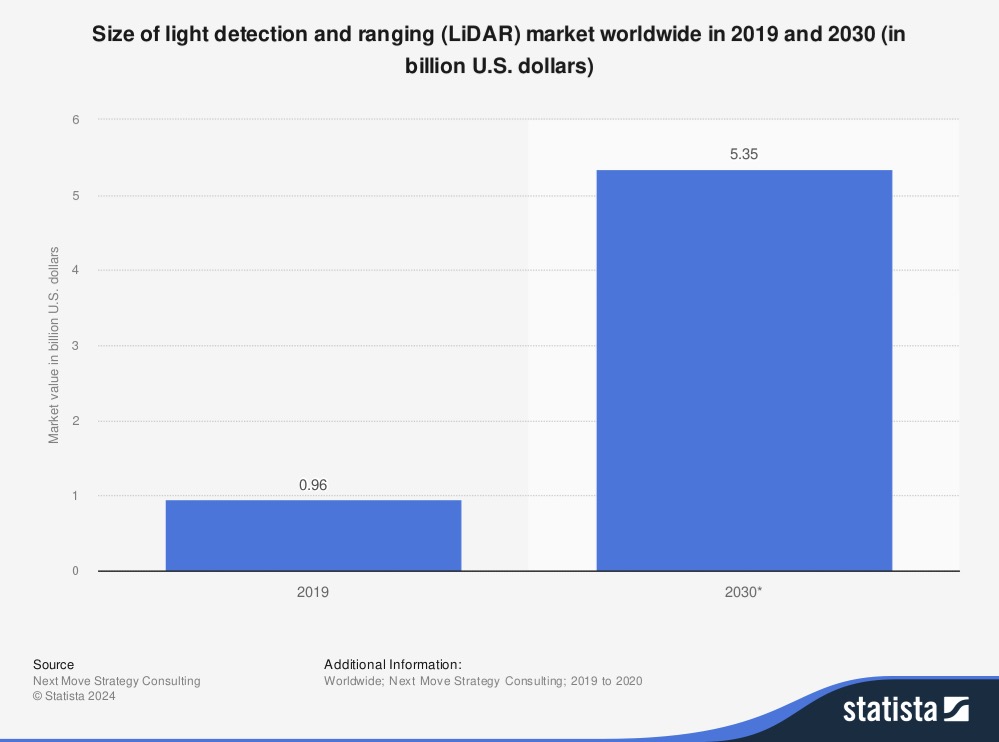

However, despite the number of crashes, customer acceptance surveys are still mixed. Results can range from not wanting autonomous driving features at all to embracing the coming change. A 2021 McKinsey study found that customers not only want autonomous driving capabilities in their private cars but are willing to pay for them. The growth in demand is predicted to create billions of dollars in additional revenue, especially for automotive companies that can reliably produce LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) Level 2+ capabilities. For the LiDAR industry, those components will be sold for about $1,500 – $2,000 per component, with additional costs for the requirements of Level 3 (L3) and Level 4 (L4) autonomy.

Since McKinsey tends to focus on executives and professionals in its global surveys, the difference in enthusiasm between survey types may be due in part to the different types of people included. In a third study conducted by Ericsson with a more diverse pool of people on the same topic, they found that 53% of working families with children expressed interest in self-driving cars, compared to only 35% of people without children who expressed no interest at all. Given that their results were only able to justify a higher level of autonomy in a very niche market, it’s likely that social acceptance would still need to improve, even if the technology for fully and safely autonomous driving were available today.

In another survey conducted by Asahi Kasei and SKOPOS, researchers also found that global markets play a large role in acceptance rates. Respondents in China tended to be more open to autonomous vehicles, while those in Germany and the United States were opposed, and consumers in Japan were somewhere in the middle. Offering a steering wheel and brakes to take control if needed also increased acceptance among those in the United States and Germany.

How are autonomous mobility companies promoting behavior change and societal acceptance?

Almost always, societal acceptance is a slow grind toward tolerance and, later, adoption. Incidents like those mentioned above, where people are injured or killed by new technology, only worsen acceptance for a period of time. Sometimes, if public acceptance is too low, as was the case of the Netherlands with the advent of cars, protesters were able to shape the future of new technologies by blocking them or changing course.

Companies like Waymo, a Google-owned company and a direct competitor to Cruise, have started to push back on the negative publicity by publishing studies comparing the accident rates of autonomous cars to those driven by humans. This is a similar strategy to the marketing done to encourage people to ride on planes. Sometimes, these phrases are used so often that they become a normal part of an industry, which is why I’m sure you’ve heard someone say before, “you’re much more likely to die in a car crash than in a plane.”

These marketing strategies are the first push to encourage people to feel safe and try out new technologies, like autonomous vehicles. In the Waymo study, they were able to prove that autonomous cars were 6.7 times less likely than human-driven cars to cause a crash, resulting in an injury.

That’s an 85 percent reduction compared to human drivers. Autonomous cars are also 2.3 times less likely to be involved in a police-reported crash. However, while these numbers sound impressive, it’s important to keep in mind that Waymo’s cars are geofenced and don’t drive on highways, which could help reduce the potential for more serious accidents.

Marketing departments are basing their studies and numbers on traditional intentional behavior change studies, which were established in the 1970s and 1980s. If we look closely, there are five distinct stages that can be used to guide people to adopt new behaviors:

- Pre-contemplation: The first part of the process where someone is considering changing their behavior but does not yet intend to take action.

- Contemplation: When the person begins to prepare to take possible actions to change their behavior.

- Action: When the first action toward the desired behavior change occurs.

- Maintenance: The action has been taken to change behavior and will be maintained for a period of time.

- Termination: The person decides that the behavior change is no longer desired and returns to a previous behavior.

Going through this process quickly in a hypothetical autonomous bullet train situation, someone might first notice a possible autonomous bullet train for their route. Stage two would be considering booking the autonomous train instead of the regular train. This would generally be motivated by either the cost or the reduced time needed to get there. They’d probably be moved to act based on how well the train has performed in the past or based on studies showing that it’s safe.

If we want to see the step of termination, we can go back to the example of the Boycott Tesla ads during the 2024 Super Bowl. The organization behind the ads attempted to show that, because of the accidents caused by the autopilot, the behavior of driving autonomous vehicles should no longer be considered desirable.

By following a more successful model of behavioral change, companies have already started to guide people to try autonomous mobility options. For example, when Denmark announced their autonomous metro, they had the Queen of Denmark take the first ride in order to increase the rate of acceptance. By having a well-known public figure take a ride on the new metro, it allowed people to see that it was likely really safe, and also something they would also consider doing.

In Sweden, the company Torghatten has also launched a captainless ship and is guiding the change in behavior with standby captains who can take control of the ship if the autopilot system fails or malfunctions. Even though they do not have their hands on the controls, many passengers have a much greater sense of security, knowing that they will be safe in the event of a malfunction. The goal for Torghatten is to eventually phase out the captain as people begin to feel more comfortable with the technology.

Even autonomous air taxis are getting ready to be used for the first time at the Paris Olympic Games in 2024 by the company Volocopter. These air taxis are actually called eVTOLs, which stands for electric vertical take-off and landing (aircraft). Volocopter’s eVTOL, Volocity, was designed to be fully autonomous. However, the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) has not yet issued regulations to allow this, yet. As a result, the Volocity will have a pilot on board who will have the authority to perform autonomous functions like speed control or already approved uses of the autopilot. For passengers, this may feel more like riding in a less noisy version of a helicopter with nicer landing pads (for urban air mobility, these are actually called vertiports).

Although autonomous cars are currently facing more backlash due to the accidents that have occurred in the past few years, companies like Waymo continue to offer autonomous taxi services. If they can continue without major incidents, it’s likely that more people will consider using them over human-driven alternatives. Of course, Waymo currently doesn’t charge users for rides, which also helps the company’s adoption rate in comparison to traditional transportation alternatives in San Francisco.

The role of regulatory support for the adoption of autonomous mobility

Changing consumer behavior won’t be enough on its own if the autonomous mobility industry wants to see an impact on the way we travel in the next few decades. They will need to work closely with regulators to allow for a relaxation of regulations that will enable them to operate at scale.

While EASA is currently working with the urban air mobility industry to unlock flights, as evidenced by its approval of Volocopter flights during the Paris Olympics, The World Forum for Harmonization of Vehicle Regulations (WP.29) is attempting to do the same for autonomous vehicles. It’s a unique forum established by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). Its purpose is to define technical regulations for vehicles, vehicle parts, and equipment to make global trade easier, greener, and safer. They’re also responsible for creating the regulatory framework needed to introduce new and innovative technologies, including those found in autonomous vehicles.

The current state of autonomous vehicle regulations is being developed by the Working Party on Automated/Autonomous and Connected Vehicles (GRVA), which is another group within the UNECE. They’ve been working on unlocking Level 3 autonomy for autonomous vehicles, which allows for complete automation but still lets a driver take back control if needed.

For now, autonomous vehicles can only be activated under certain conditions, such as on roads with no pedestrians or cyclists. However, some progress was seen in the summer of 2022 when they approved a speed increase from 60 km/h to 130 km/h for current autonomous vehicles.

Because the conditions for autonomy are very different for ground and air vehicles, autonomous maritime vehicles are a bit behind the curve. Even so, the European Commission is hosting an annual International Ship Autonomy and Sustainability Summit to discuss the progress being made in the industry, including the regulatory hurdles, with the 5th edition taking place in 2024. If you’re curious about the tone of the event, the European Commission released the introductory video for the 2nd conference in 2020, which is worth checking out.

Smart cities and the potential for autonomous mobility

Cities can also provide more accessible and climate-friendly options for their citizens by enabling autonomous mobility. Autonomous ride-sharing, if cheap and efficient enough, could offer a huge advantage over traditional fossil-fuel-powered mobility. What’s more, they do not require additional infrastructure in already overcrowded cities where urban real estate is hard to find. For smart cities, this is one of the biggest challenges they face since it makes adding additional trams, metros, or trains nearly impossible.

These technologies are also essential to even be considered as a smart city, according to the European Commission:

A smart city goes beyond the use of digital technologies for better resource use and less emissions. It means smarter urban transport networks, upgraded water supply and waste disposal facilities and more efficient ways to light and heat buildings. It also means a more interactive and responsive city administration, safer public spaces and meeting the needs of an ageing population.

Faced with the challenges of overcrowding amid a decade of population decline, Paris is actively exploring partnerships in innovative transportation solutions, such as urban air mobility, to alleviate congestion. The potential of these new transportation methods to address urban challenges is highlighted by a 2022 study, which showed that autonomous vehicles could provide significant benefits in densely populated cities — including Paris, New York, and Shanghai.

Still, adding new transportation options to these dense urban centers is often really complicated. This is largely due to the highly competitive nature of real estate. That’s why modifying existing infrastructure, such as subways or train systems, can take decades and often lag behind the rapid pace at which cities evolve. This dynamic nature of urban growth is in complete opposition to the slower decision-making processes and construction, which is why emerging mobility is often seen as the fastest solution.

As autonomous mobility and systems become more widespread, we’ll likely see a number of improvements: less traffic and pollution in cities as cars stop sitting idle and burning unnecessary fuel, and more space in cities themselves as parking requirements are reduced. There is also the possibility of implementing city-wide autonomous traffic control systems as the use of autonomous vehicles in cities continues to grow. This would be similar to the air traffic control system, where air traffic controllers at airports plan flights for airplanes. Because there are so many decisions to be made, traffic management in a smart city would need to be controlled by artificial intelligence. Fortunately, companies like HHLA Sky are already developing this technology with their Integrated Control Center, which can plan routes for autonomous robots at sea, on the ground, and in the air.

Startups reshaping the world of autonomous mobility

With the potential to expand beyond smart cities, traffic control systems could also be a game-changer for the autonomous freight industry. With trucks currently transporting 70% of all freight in markets such as the United States, the development of new freight vehicles capable of operating across the country has the potential to alleviate the growing pressures on the industry from labor shortages, ever-increasing demand, and competitive pricing.

The Daimler-supported startup Torc (2005) stands out as a key achievement in this area. The company is leading efforts to test Level 4 autonomous trucks on highways. Designed to operate autonomously, requiring human drivers only for the last mile in populated areas, these trucks reduce the workload on existing drivers while allowing companies to quickly scale operations and expand their fleets.

Fraction (2020) is also developing autonomous vehicles and software to help companies deliver goods and provide improved last-mile transportation solutions. The company aims to make a positive contribution by providing more efficient and versatile transport and delivery options through the combination of its range of vehicles and software.

Fraction’s main competitor in this space is Nuro (2016), which also offers a similar range of autonomous vehicles. These are developed and offered to companies looking to add the technology to their existing fleet. The company did face a wave of layoffs in 2023. However, they’re now switching focus to research and development to prepare the technology for the future.

More recently, HYDRON (2021), similar to Torc, has been in the works as a future contender in the freight truck industry. The main difference is that HYDRON is hydrogen fuel cell powered, making it one of the first climate-friendly autonomous freight options on the market.

Finally, the last startup to keep an eye on is Germany’s Scantinel (2019), which is in direct competition with the world’s largest LiDAR provider: Luminar (2012). Scantinel aims to develop stationary LiDAR (without moving elements) with enhanced scanning capabilities specifically for autonomous vehicles.

Do you have a unique, non-obvious solution that addresses today’s autonomous mobility challenges? Share your idea with us, and we may be able to provide the support you need to turn it into a startup!